To reject the machine made and embrace handicraft, to take nature as inspiration, to advocate for social reform: the Arts and Crafts movement of the 19th and early 20th century celebrated a return to preindustrial production to improve people’s lives by integrating art and design objects into everyday life. A revival of the past to improve the present? Sounds like us!

As we are burnt out from the conversations surrounding burnout, are toggling between Zoom and IRL meetings and want a vacation from our vacations, the desire to slow down, celebrate nature and respect labor also sounds like us. Recognizing the parallels in our lives across centuries, the Edith Collection offers four new rugs which take design and philosophical inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement.

The Arts and Crafts movement emerged in England and North America as a response to the alienating effects of the mechanized, modern world. People like William Morris and John Ruskin - stalwarts of the movement - were concerned about the social repercussions of the replacement of humans by machines. It may have started over a hundred years ago, but these fears sound pretty apt today. In the face of these anxieties, proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement championed the designer as a craftsperson who made individual objects by hand, with attention, detail, care and purpose.

Adhering to a principal tenant of the movement, the Edith Collection is entirely handcrafted. Developed over 6 months, talented artists in India meticulously knotted together New Zealand wool into organic shapes in calming, vintage colors. It takes time, patience and incredible skill to make a hand knotted rug. Expert weavers sit at looms, wrapping warp yarns across wefts to generate each individual knot in each individual rug. Slowing down to celebrate the work of skilled craftspeople is a necessary antidote to the rush of contemporary life.

We also know that while a history lesson can help us fill in some blanks, at the end of the day a handcrafted rug just feels different. Nestling our feet into a handmade rug reminds us of holding our grandma’s sweater, or cradling the paperweight that belonged to her father. The desk we found in a thrift store, and the vintage typewriter that sits atop it even though we have a Macbook pro – living with these objects brings a sense of integrity to one’s home, a weightiness of history coupled with an embodied and personable tactility that envelops and connects you to the world outside and across eras.

This playful game of historic hopscotch is visually coded into the Arts and Crafts movement. Many notable designers, such as Gustav Stickley, May Morris and Charles Rennie Mackintosh looked to the Medieval era for creative inspiration citing their use of clean lines, organic forms, and natural subjects. Our Mackintosh rug evokes the mood of a Gothic church, with triangles and rhomboids as simplified vaults and arches studding a warm, taupe, wooden interior. Is the deep rust and sage recurring pattern of the Milord rug a flower? A stained glass window? Our contemporary take on these motifs refers to our Arts and Crafts predecessors, and then back again to their even earlier influences.

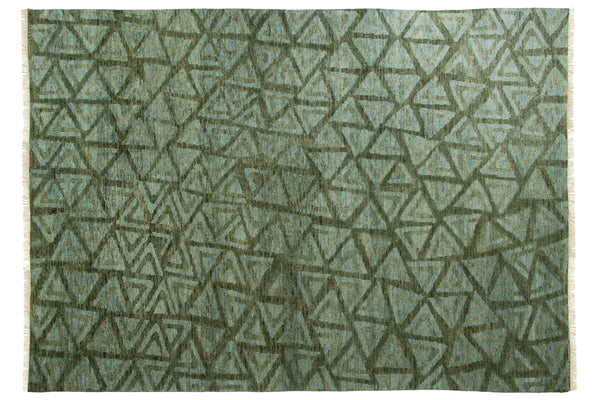

The influences are also global. The Ukiyo and Rennie rugs play with soft triangles in ochre and foggy sage tones that repeat as slightly askew, as if hand stamped. With their innovative use of negative space and oblique nod to block print technology, these rugs reflect an interest in Japanese art and culture that swept America and Western Europe in the mid 1800s, referred to as Japanism. International trade recommenced, and Arts and Crafts designers with access to Japanese goods were deeply influenced by what they saw broadly as Japanese appreciation for natural forms, minimalism and asymmetry in the design of functional objects. The golden and brown triangles of the Ukiyo overlap at gentle angles, creating a composition that is not uniform, yet is balanced. Rennie wittily plays with background and foreground, turning triangles to create a maze of lines that run right off the rug - poetically integrating art with life.

Rennie —shop here

One of our favorite examples of the intersection of art and life encouraged by the Arts and Crafts movement is the formation of the Saturday Evening Girls Club (SEG) by the librarian Edith Guerrier. Around the turn of the 20th century, young women, mainly immigrants who landed in Boston around the turn of the 20th century, gathered together to form a book club led by Guerrier. As the group grew in size it also expanded in scope, and Guerrier encouraged girls not only to read but also to participate in a wide array of artistic endeavors including ceramics. Eventually, Guerrier opened a storefront to sell pottery made by the SEG, providing income to a historically overlooked population and producing hallmark products of the Arts and Crafts movement known as Paul Revere Pottery. We admire Edith Guerrier so much that we named our collection after her.

Across the Arts and Crafts movement, advocating for the artisan was tied to a broader belief that art should be integrated into everyday life and not just relegated to paintings on museum walls. In other words, those who make furniture, textiles, and household wares should be elevated and respected like those who show work in gallery settings. If this rhetoric sounds familiar, it’s because it influenced a slate of 20th century designers, perhaps most notably the Bauhaus. We are happy to say their philosophies also influenced us. The women in the SEG, like our collaborators in India, are valued as artists whose wares improve our daily experiences. Morris’s enthusiasm for aesthetic, functional objects translated into day to day life, as he famously encouraged the population to, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.”